You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘wrestling with God’ tag.

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, August 3, 2014, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: Genesis 32:22-31

Copyright © 2014 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

Two weeks ago, we heard part of the Jacob saga recorded in Genesis. We heard the story of Jacob, running from his brother Esau after stealing the elder son’s blessing from their father, when he stopped to sleep. We heard how he had a dream of a ladder connecting where he was with heaven, a ladder that angels climbed and descended.

The saga continues, and today we hear about a wrestling match. Jacob is facing a time when he will likely be confronting his brother again. What will he do? Jacob’s family had grown. He has two wives, two concubines, 11 sons, and presumably some daughters. He has wealth and power. And if you’re familiar with the story, you’ll remember that he grew his family and his wealth by manipulating his father-in-law, maybe even cheating his father-in-law.

But Esau’s family has grown, too. He, too, has wealth and power.

Knowing that the day was coming when he would have to confront Esau again, Jacob sent presents to Esau to try to appease him. And now Esau is coming and who knows what Esau’s agenda is. It could very well be revenge. He could still be holding a grudge. So, what is Jacob to do?

He sends his family to the other side of the stream. That provides a little bit of protection, and it provides Jacob with a little privacy. And all night, Jacob wrestles.

The text says that “a man” wrestles with Jacob. By the end of the story, Jacob declares that he has seen God face to face. Whoever it is that Jacob wrestles with, he understands it to be God.

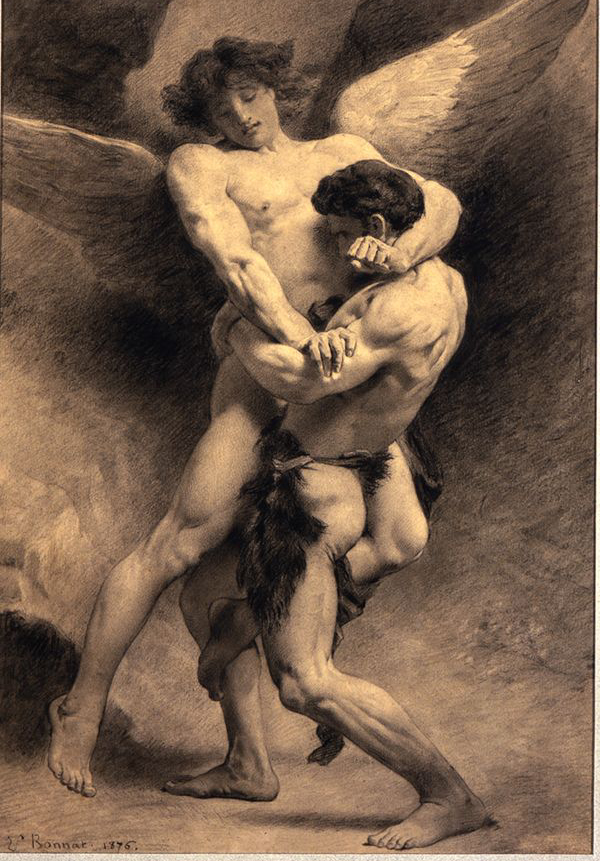

Like many great stories, this chapter in the Jacob saga has inspired many artists. On the cover of your bulletins, you have “Jacob Wrestling the Angel” by Léon Bonnat, a 19th century French artist. I find it interesting because it captures the physical struggle, with muscles and sinews straining. We don’t see Jacob’s face, so he can be an “every man” – well, an “every European man;” both he and the angel seem pretty white to me. And, in this moment at least, Jacob seems to be winning. He has the angel – and it’s very clearly an angel with the wings – off the ground. The angel’s only defense is a foot hooked around one of Jacob’s legs.

As I looked for art for our bulletin cover, I was impressed to find contemporary artists still creating, inspired by this story. I’m a bit amused by some Marc Chagall’s paintings on the subject where the angel is twice the size of Jacob.

Another piece in particular intrigued me, but because it’s copyrighted, I wasn’t comfortable printing it.[1] Painted by local artist Suzanne Giuriati-Cerny, the painting has three figures in it – three men in a story that only has two men in it. I think two of the men, and possibly the third are the same person. This particular painting makes me think about the possibility of Jacob wrestling with himself, of understanding the God with whom Jacob wrestles as not being “out there,” but as being inside, within.

Think about that idea. When we have an internal struggle going on, could we be, are we likely to be wrestling with God? I think so. And I think that this internal struggle is a universal part of human experience. Sister Joan Chittister reflects on the value, the importance of this struggle:

“The process of struggle is the process of the internal redefinition of the self. People do it in the midst of a marriage that is failing on one set of expectations and in need of being renegotiated around others. People do it when the work they do ceases to be for them what they expected it to be. People do it when they find themselves locked out socially of the very places they want to be in life: in the midst of the dominant culture, in a position of power and authority, in a place of comfort and security. When our expectations run aground of our reality, we begin to rethink the meaning and shape of our lives. We begin to rethink not just our past decisions but our very selves. It is a slow but determining deconstruction of the self so that a real person can be reborn in us, beyond the expectations of others, even beyond our own previously unassailable assumptions. And struggle is its catalyst.

“The Hebrew Testament story of Jacob wrestling with God is a model of the process. It is given to us to apply like a template to our own lives. Each element of the small vignette is a warning call to us to attend to what God is allowing to happen to us here and now so that we might go on even healthier in times to come. It provides a series of checkpoints for the spiritual life. It is in itself a veritable spirituality of struggle, which exposes to us those elements of suffering that call us to growth and give us new life.”[2]

Dan Buchanan and Amy Carr connect the struggle Jacob faced at the ford of the Jabbok with wrestling with the demonic. Now, they’re not talking about the demonic powers that make people think it’s okay to shoot airliners out of the sky, or the demonic powers that encourage us to embrace militarism as a way to peace, or the demonic powers that justify the chasing of an entire race or religion or ethnicity out of their homes.

No, they are talking about the power of restlessness, which they call demonic the way third and fourth century Christian monks of the Egyptian desert did. “When they [the desert fathers] were at work, they felt drawn to prayer; when they prayed, they felt drawn to work; when they settled in one monastery, they became convinced that true spirituality could be found only in the monastery down the road. Because such feelings struck hardest in the middle of the day, monks associated them with the ‘noonday demon’ in Psalm 91. The monk’s task was not to flee from this demon, but to stay put and wrestle with it.”[3] They suggest that wrestling with this restlessness is a path to a blessing. “Restlessness,” they say, “signals God’s draw on our lives, and no single commitment curbs that restlessness unless it is oriented to the larger horizon of God’s magnetic love.”[4]

So, don’t run away from the restlessness; wrestle with it. Listen to it. Create a space of silence – whether through centering prayer or long walks or quietly washing the dishes – that will allow you to listen.

A big “aha” for me about this scripture came from an article by Rabbi Arthur Waskow. (Very definitely, one of the perks of my job is that I get to – in fact, that I’m expected to read articles and commentaries on scripture.) Waskow reads the Jacob saga in the wider context of the book of Genesis. He hears in Genesis one theme with many variations: “war and peace between brothers (and one pair of sisters).”[5]

The war between the brothers begins with the very first brothers, Cain and Abel. “Abel, the second-born child whose name means ‘Puff of Breath,’ and Cain, the first-born whose name means ‘Possessive,’ bring offerings to God – the fruit of their labor in field and pasture. Abel’s offering is accepted, Cain’s is rejected.

“Cain is angry—what else would you expect? But he says nothing.”[6] God reaches out to him repeatedly, but Cain is silent. Instead Cain goes to his brother. The Bibles says, “Cain said to his brother Abel, ‘Let us go out to the field.’” Except that some of the authoritative manuscripts don’t have “Let us go out to the field.” It’s as if Cain wanted to say something but he couldn’t get the words out. And instead of speaking to his brother, Cain kills him.

The older brother kills the younger brother out of a sense of anger or jealousy because it seems as if God likes the younger brother better. God reached out to the angry, jealous Cain, but Cain wouldn’t engage. Cain wouldn’t challenge God, answer God, wrestle with God. Cain wouldn’t grow up, and he killed his brother. “It is only when Jacob learns to wrestle God that it becomes possible for him to make friends with his brother.”[7]

Waskow points out how this motif of older and younger brother in opposition keeps coming up. Ishmael verses Isaac. Esau verses Jacob. Even two sisters, Leah and Rachel, turn against each other. Even though they both end up married to Jacob and together bearing him twelve sons and several daughters, they are unable to find a reconciliation. And then there is the rivalry among those 12 sons, the rivalry between Joseph and his older brothers. It is a story of hatred, fury, plotting, and almost murder.

This string of rivalries finally ends, Waskow notes, with Joseph’s two sons, Ephraim and Manasseh: “Jacob, their grandfather, insists on blessing them. Jacob, who had fooled his father into giving him the first-born’s blessing, leaps across a generation to end the collision over firstbornness. Jacob, who has learned how to stop wrestling with his brother and wrestle with God instead, shows Manasseh and Ephraim how not to wrestle with each other.

“Jacob recognizes and affirms his own victory over his first-born brother by reversing the hands with which the blessings should be given. The right hand – the first-born’s hand – he reaches out to Ephraim, the second-born. The left hand – the second-born’s hand – he reaches out to bless Manasseh, the first-born.

“But in the same moment he dissolves the tension, for he blesses them simultaneously, with a single blessing. Lest they miss the point, he literally crosses his arms to bless them ‘backwards’ and explicitly rejects Joseph’s objection that he has it wrong. And he blesses them both in the same breath, saying ‘By you’ – a singular you, each of them singularly at the same instant – ‘shall Israel bless, saying, God make you as Ephraim and as Manasseh.’”[8] Wrestling with God, as Waskow reads the story, is a path to reconciliation.

Back a couple months ago when I was selecting scriptures and sermon themes for the Sundays in August, I knew I wanted to preach on this lection. I knew I wanted to I talk about the merits of wrestling with God as a spiritual practice. That’s the invitation I hear in this story. When our realities don’t live up to our expectations and we need to rediscover who we are, when our restlessness draws us away from the stillness we need to discern our vocation, when our anger and jealousy and fear keep us estranged, we need to engage in the spiritual practice of wrestling with God.

Richard Pervo asks an important question about wrestling with God: “What kind of god will get into a nighttime brawl with a mortal and come out no better than even?”[9] That’s what happens in the story. Jacob and this stranger who Jacob comes to understand is God wrestles all night, and Jacob prevails because he is able to limp away.

When you think about the wrestling we need to do with God, when you think about our need to rediscover ourselves, when you think about our need to hear what our restlessness is trying to tell us, when you think about the estrangements in our lives that need reconciliation, then maybe you’ll agree. The kind of god who will get into a nighttime brawl with a mortal and come out no better than even is exactly the kind of God we need.

Amen.

ENDNOTES

[1] See http://fineartamerica.com/featured/jacob-wrestling-with-the-angel-suzanne-cerny.html

[2] Joan C. Chittister, Scarred by Struggle, Transformed by Hope: The Nine Gifts of Struggle, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2003), reprinted by Sojourners on http://sojo.net/preaching-the-word/gift-struggle (accessed 28 July 2014).

[3] Dan Buchanan and Amy Carr, “Called to the Everyday,” Sojourners, http://sojo.net/preaching-the-word/called-everyday (accessed 28 July 2014).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Arthur Waskow, “Brothers Reconciled,” Sojourners, http://sojo.net/preaching-the-word/brothers-reconcilied (accessed on 28 July 2014).

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Richard Pervo in New Proclamation Year A 2011, quoted by Kathryn Matthews Huey, “Sermon Seeds,” United Church of Christ, http://www.ucc.org/worship/samuel/august-3-2014.html (accessed 28 July 2014).