A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, April 28, 2024, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: John 21:1-8 and Mark 5:24-34

Copyright © 2024 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

It’s so easy to get this church thing wrong. It’s so easy to get caught up in the institution, in the preservation of what was, in power and property. Maybe more so for me than for you, since my position is rather institutional.

I’m thankful when I get reminders that the church thing is supposed to be a mirror of the Jesus thing. And a reminder of what Jesus was about. That’s what happened last week. I got to read a sermon that Nadia Bolz-Weber preached at the ordination of one of her dear friends. In that sermon, she told a story:

“It’s Easter Sunday and I am worshipping inside the Denver women’s prison, and during one of the songs, my mind wanders … The band is playing and I am staring distractedly at our altar, a square plastic table which, each Sunday, is adorned with hand-me-downs from churches that have closed. I stare at the cheap faded yellow satin on the table in front of me; janky frayed letters sewn on its front spell out alleluia.

“‘God knows what decade that was made,’ I think to myself. ‘Maybe the 60s when it and whatever the now defunct congregation who donated it was still full and shiny.’

“And then I realize that surrounding me are 175 women in prison greens singing:

If you’ve got pain, he’s a pain taker.

If you feel lost, he’s a way maker.

If you need freedom or saving, he’s a prison-shaking savior.

If you’ve got chains, he’s a chain breaker.

Which is when I remember that this [church] thing has never been about power and institutions and property. It’s never been for the proud. It’s always been about God uplifting the humble and feeding the hungry and forgiving the sinner. Afterall, Jesus said he came for the sick and not the well.”[1]

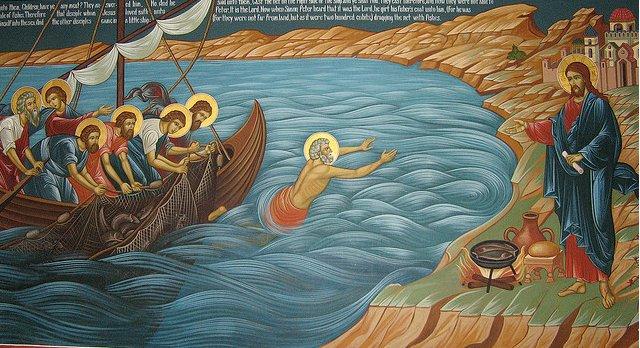

I think both of our scripture readings point to Jesus’ healing ministry – and in very different ways. The resurrection story from John’s gospel doesn’t look like a healing story, at least not at first glance. This account takes place maybe a couple weeks after that first Easter morning. A group of the disciples are hanging out. John doesn’t tell us where they are, but later we learn that it has to be evening or maybe even after sundown. Peter announces that he’s going fishing, and the group says they’ll go with him. Hey, at least they aren’t keeping themselves locked away in their fear.

What they’re doing here, I think, is going back to the familiar, going back to something concrete, going back to something they knew and understood. Nobody’s childhood is pain-free, and some childhoods are downright traumatic. All of us develop coping mechanisms that help us survive whatever pains we go through as kids. And when we become adults, it is really easy to go back to those coping mechanisms when we’re dealing with something painful, even though we have new skills for dealing with painful situations.

That’s the sort of thing I see happening here. Peter, Andrew, James, and John were fishers before Jesus called them. Here, even after spending time traveling with Jesus and being formed by Jesus, they go back to fishing. Jesus’ crucifixion (which was a traumatic thing to go through, even if these guys didn’t witness it directly) would push a button and make them turn to an old coping mechanism. Even though they’ve had experiences of the resurrected Jesus being in their midst, those are confusing experiences and difficult to explain, maybe even disconcerting enough to bring on an old coping mechanism response.

So Peter announces he’s going to do a thing he knows how to do. He’s going fishing. And a bunch join him. They fish all night and catch nothing. And Jesus shows up on the shore of the lake. He calls out to them, confirming that they haven’t caught anything, and he tells them to try casting their net on the other sides of the boat. And their net is so full of fish they can’t haul them in.

Jesus’ advice is about more than just fishing. This is a healing story. By meeting them at the lake at daybreak, Jesus helps them heal from their old patterns and coping mechanism, calling them to new ways of being and coping in the world.

The story in the passage from Mark is more obviously a healing story. A woman “had been suffering from a flow of blood for twelve years. She had endured much under many physicians and had spent all that she had, and she was no better but rather grew worse.”[2]

I’m sure there are people in worship today who have had a similar experience with the medical industry. You’ve had a medical problem. You’ve done what you can. You’ve sought the advice of doctors and specialists. And things just haven’t gotten better. In fact, in some ways things have gotten worse.

The woman in the story “had heard about Jesus and came up behind him in the crowd and touched his cloak, for she said, ‘If I but touch his cloak, I will be made well.’”[3] So, in the press of the crowd, the woman claims her own agency and reaches out and touches Jesus’ cloak. And she is healed.

There are some wonderful contrasts in these two stories. First, there’s the contrast between who sees what needs to be done. In the Mark story, the woman sees she needs to touch Jesus’ cloak. In the John story, Jesus sees where the disciples need to fish.

The contrasts continue. In Mark’s story, the woman knows what to do. In John’s story, the men need Jesus to tell them what to do. In Mark’s story, the miracle happens internally, inside the woman’s body. In John’s story, the miracle happens externally, out in the lake in the fishing nets. In Mark’s story, the woman sees Jesus and that leads to the miracle. In John’s story, the miracle happens and that leads to the disciples seeing Jesus. In Mark’s story, Jesus heals by taking something away (the woman’s illness). In John’s story, Jesus heals by giving the disciples something (fish). Mark’s story takes place mid-day. John’s story takes place just as dawn is breaking.

Many thanks to Cindy Sojourner for helping us notice all these contrasts at last Monday’s Monday Morning Bible Study. Here’s my big take-away from all these contrasts: Jesus’ healing resurrection powers are ready to work anywhere, at any time, with anyone.

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. A friend recently wrote a poetic reflection about her mother entering hospice. Her father died not too long ago after a long journey with dementia. Her mother also has dementia and her journey has moved much more quickly. Here’s some of Reena’s reflection:[4]

You’ve been fading for a long time but you’ve also been reemerging as well.

Your past self, burdened with resentment and frustration and grief, seemed to be dissipating and in its place blossomed a new version of you.

This you was softer, lighter, more joyful.

This you was open and free with your love, rather than conditional and closed off.

I’ve lost count of the many beautiful things you’ve said to me these last months.

Things I never thought I’d be lucky enough to hear from you.

Things you had such a hard time saying before:

You’re so wonderful.

You girls, you’re like Wonder Woman!

Thank you so much sweetheart.

You’re so beautiful.

I’m so grateful for you.

The sweet words spill so freely from your lips I have a hard time believing you ever struggled to utter them.

I can’t believe how blessed I am to have had this time with you.

So many people never get the chance to heal relationships in their lifetime.

To witness change and healing in someone they love.

To experience adoration and gratitude where it had not been expressed before.

I’m so lucky, I know.

Why doesn’t that make this easier?

Reena has found and is finding healing during this hard, hard, holy time. She might not identify it as the resurrection power of healing. The language of her spirituality isn’t so traditionally Christian. Still, that’s what I see. I see Jesus, at this strange time and in the strange circumstances of Reena’s life, welcoming her touch. I see Jesus giving her what she lacks and needs in this moment.

For five years or more, there’s been a story floating around the Internet that is commonly attributed to A.A. Milne. It is almost certainly not his work, though it was written in his style. More likely, it is the work of Kathryn Wallace.[5] Nonetheless, the story is sweet and it reminds us that we can sometimes me the means Jesus uses to bring healing.

It occurred to Pooh and Piglet that they hadn’t heard from Eeyore for several days, so they put on their hats and coats and trotted across the Hundred Acre Wood to Eeyore’s stick house. Inside the house was Eeyore.

“Hello Eeyore,” said Pooh.

“Hello Pooh. Hello Piglet,” said Eeyore, in a Glum Sounding Voice.

“We just thought we’d check in on you,” said Piglet, “because we hadn’t heard from you, and so we wanted to know if you were okay.”

Eeyore was silent for a moment.

“Am I okay?” he asked, eventually.

“Well, I don’t know, to be honest. Are any of us really okay?

That’s what I ask myself.

All I can tell you, Pooh and Piglet, is that right now I feel really rather Sad, and Alone, and Not Much Fun To Be Around At All.

Which is why I haven’t bothered you.

Because you wouldn’t want to waste your time hanging out with someone who is Sad, and Alone, and Not Much Fun To Be Around At All, would you now.”

Pooh glanced at Piglet, and Piglet glanced at Pooh, and they both settled, one on each side of Eeyore in his twig abode.

Eeyore looked at them in surprise. “What are you doing?”

“We’re sitting here with you,” said Pooh, “because we are your friends. And true friends don’t care if someone is feeling Sad, or Alone, or Not Much Fun To Be Around At All. True friends are there for you anyway. And so here we are.”

“Oh,” said Eeyore. “Oh.”

And the three of them sat there in silence.

And while Pooh and Piglet said nothing at all, somehow, almost imperceptibly, Eeyore started to feel a very tiny little bit better.

Because Pooh and Piglet were There.

During this time of reflection, I invite you to consider these two questions: Has this look at the resurrection power of healing unlocked one of your resurrection stories? How might you speak up and share this good news?

[1] Nadia Bolz-Weber, “Who’s this whole thing FOR, anyhow?” The Corners, https://thecorners.substack.com/p/who-is-this-whole-thing-for-anyhow (posted 7 April 2024; accessed 22 April 2024). Some grammatical corrections made.

[2] Mark 5:25-26, NRSV.

[3] Mark 5:27-28, NRSV.

[4] Reena Burton, “Hospice,” Tender Heart, https://tenderheartedgirl.wordpress.com/2024/04/24/hospice/ (posted and accessed on 24 April 2024).

[5] “Fake Poohs,” English Wanted, https://englishwanted.com/editing/fake-poohs/ (posted 27 August 2019; accessed 13 April 2024).