You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Mary’ tag.

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, March 26, 2023, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: John 11:1-45

Copyright © 2023 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

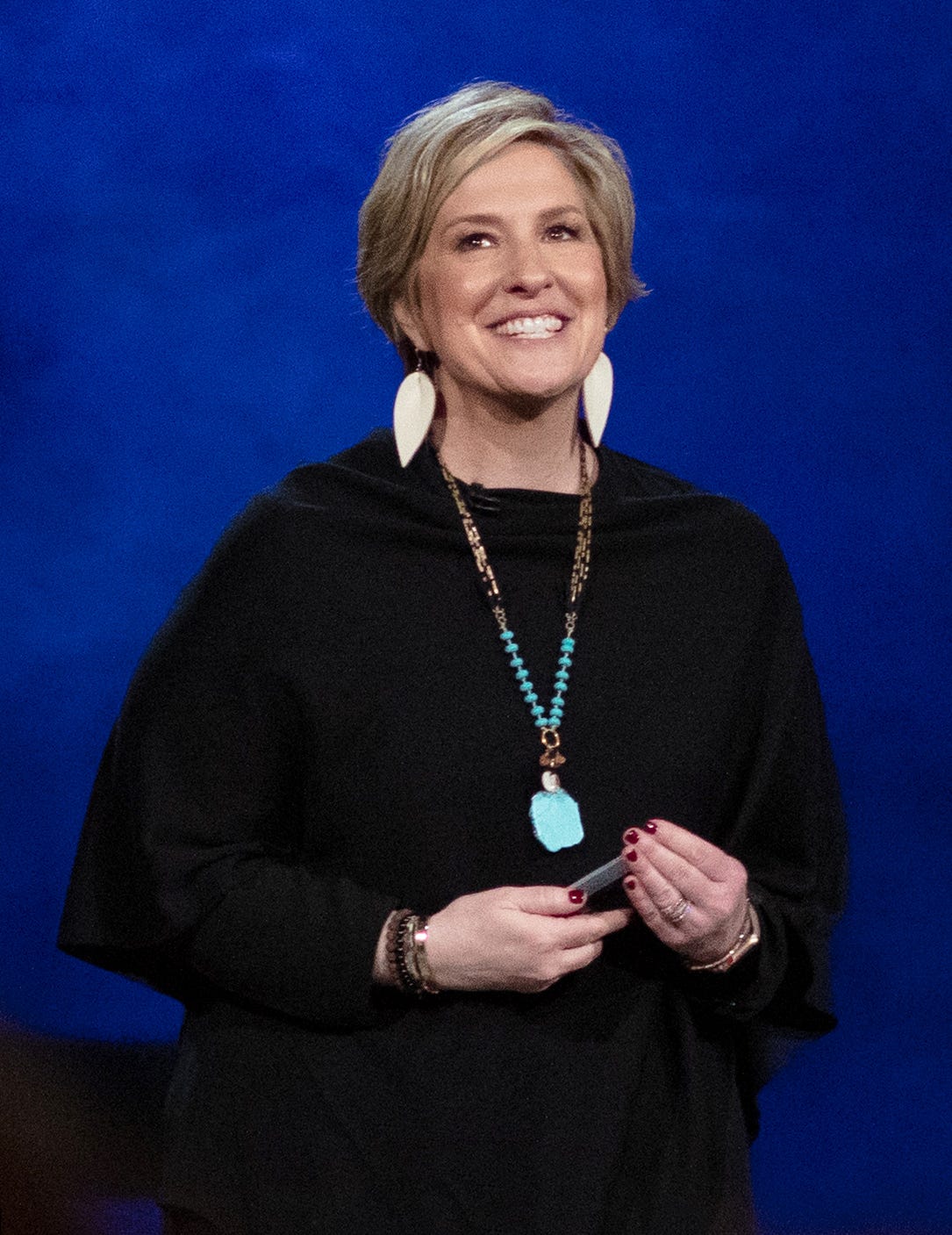

I got to have a wonderful theological geek-out 10 days ago. That day, I got to attend a webinar starring (is that the right word to use for a webinar?) Elizabeth Schrader.[1] If you been attending worship regularly for the past year, you heard both Pastor Brenda and me talk about Libbie Schrader’s amazing work on the Gospel of John. Her doctoral dissertation, which I think has been submitted now, examines some inconsistencies in the manuscripts of the Gospel that go all the way back to about 200. In particular, she noticed that sometimes words have been crossed out and changed or otherwise edited especially in the eleventh chapter of the Gospel – which is today’s gospel lesson.

Here’s a concrete example. Papyrus 66 – generally thought to be the oldest near-complete manuscript of the Gospel of John and dates from around the year 200 – the word ‘Maria’ (translated ‘Mary’) has sometimes been altered, with the Greek iota symbol – the ‘i’ – scratched out and replaced with a theta – the ‘th’ sound – changing the name from Mary to Martha. In a later verse, a woman’s name was replaced with ‘the sisters.’

Seeing this a few years ago, Schrader started doing a lot more digging. At this point, she’s scoured hundreds of manuscripts of the Gospel of John and the writings of early church leaders, and she is convinced that Martha, the sister of Mary and Lazarus we heard about in today’s lesson, is an addition to the Gospel.

As an example, Schrader shared how she reconstructs John 11:1-5 by using three ancient manuscripts: Codex Alexandrinus (5th century Greek, held in the British Library) as it read before it was “corrected” for John 11:1-2; Papyrus 66 (early 3rd century Greek, held in Geneva) as it read before it was “corrected” for John 11:3-4; and Codex Colbertinus (6th century Latin manuscript, held at the Bibliothèque nationale de France) for John 11:5, which is uncorrected. Here’s the New Revised Standard Version on the left and the Schrader reconstruction on the right.

Take out Martha from the way the story is currently translated, and the story in John 11 more starkly parallels John 20 where John writes about the resurrection of Jesus. In both stories, a stone is rolled away and the one who was buried in the tomb comes back into life. Take out Martha and Mary is the one weeping outside Lazarus’ tomb in John 11, just like Mary Magdalene is outside a tomb, crying, in John 20.

Tertullian (considered to be one of the early church fathers who lived about the same time as Papyrus 66 was written) says it’s Mary who gave the Christological confession (not Martha) in John 11: “I believe you are the Messiah, the Son of God, the one coming into the world.” In other words, Tertullian contradicts the two-sister version we have now, which suggests the manuscript(s) of John he read had only one woman there: Mary. (This, Schrader says, is true of the writing of other church fathers, too.)

And if you look at early church artwork, you get the impression that Lazarus had only one sister. For instance, when the story of the resuscitation of Lazarus is depicted on 4th cent sarcophagi, we see Jesus, Lazarus, and one woman (not two). When there is a fourth person there, it’s a dude.

All this supports Schrader’s contention that in John 11, at least originally, there were only two people in the Bethany household: Lazarus and Mary. Yes, there’s a story in Luke’s gospel about two sisters Martha and Mary. You might recall that in Luke’s story, Martha complains about how her sister Mary won’t help her with getting dinner ready. They are a different household, living in a different community (not near Jerusalem).

If you are a theological geek like I am, at this point you may be asking, why did this happen? The reason may have been as simple as wanting to harmonize the two gospels, so some scribe split Mary into two women, Mary and Martha to make John’s gospel sound like Luke’s. It could also be to reduce the importance of Mary. This might have been an agenda, especially if Mary the brother of Lazarus was understood to be Mary Magdalene, which could very well be John’s intent (though I won’t take you down that theological rabbit hole – at least not today).

If you’re not a theological geek like I am, you may be asking, so what?

Information like this can cause some to start questioning their relationship with the Bible. If the translations we have now are based on manuscripts that are riddled with “corrections” (please note the sarcastic air quotes), how are we to trust them? Meanwhile, people who long ago made peace with the Bible containing inconsistencies and who long ago accepted that we don’t have originals of any of the books and letters that are considered scripture may be wondering what difference any of this makes to our understanding of today’s lesson for us today.

For both of these groups, let me offer this insight, inspired by Libbie Schrader.[2] In John 11:4, Jesus says, “The illness is not unto death, but it is for the glory of God in order to glorify the Son through it.” Though Jesus is talking about Lazarus, perhaps we can hear these words as speaking about the text itself. This illness (of the text) is not unto death. At the beginning of his gospel, John wrote, “The light shines in the darkness and the darkness does not comprehend it.” Maybe Mary needed to be diminished in order for the text to be included in the canon. Maybe followers of Jesus weren’t ready to accept the way John wrote about Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene (and especially if they are the same person), and so this wounding of the scripture made it easier to accept.

I’ve done that sort of thing. In fact, I did it today. If you were reading along in a New Revised Standard Version as Riki read the scripture lesson, you noticed that I made some changes. John makes references to “the Jews” several times in this chapter, and I simply changed them. I didn’t want to be distracted into defending John from antisemitic interpretations today, so I simply replaced the troublesome language. That may have been unfair to do, but I did it so we could focus on what it important to me today.

If scripture is living (and I believe it is), maybe we can see the wounding of John’s gospel and its portrayal of Mary (as well as my redactions) as the gospel lowering itself to where we humans were and are. Maybe, in a way, the scripture is laying its life down for its friends – for you and for me and for our Christian ancestors. It would be a very Johannine thing to do. In John 15:13, Jesus says there’s no greater way to love than that. Perhaps the Spirit of Truth could not be received through a strong Mary in the fourth and fifth centuries. And perhaps the Spirit of Truth has problems being heard today because of antisemitism.

We still needed and need the gospel of John. We still needed and need the witness that Jesus is the Word made flesh. If the scripture needed to be wounded for our sake, how Christian is that?

And if now we can see what happened, then the scripture can be liberated and resurrected. This illness is not unto death; it is an opportunity to show the glory of God.

I love how Nadia Bolz-Weber explained Christianity in one of her books: “The Christian faith, while wildly misrepresented in so much of American culture, is really about death and resurrection. It’s about how God continues to reach into the graves we dig for ourselves and [to] pull us out, giving us new life, in ways both dramatic and small.”[3]

One of the ways God reached into a grave I had dug for myself came years ago, and it came through today’s scripture.I had heard Jesus’ call to Lazarus to “come out” of the tomb as a call to me to come out of the closet years before.It’s hard for a gay man hear a call to “come out” any other way – even if the words are on the lips of Glinda the Good Witch and she’s speaking them to munchkins. It wasn’t until I heard the second part of the call that the full liberation happened.

If you read it carefully, you’ll notice that Jesus’ command has two parts. First, he calls Lazarus to come out of the tomb. Then he calls the people to unbind him. Lazarus had work to do, certainly. The community had work to do, too – the liberative work of unbinding.

That’s one of the reasons being an Open and Affirming church is so important. Embracing that identity as a congregation says to LGBTQ+ people that we have done and continue to do the liberative work of unbinding. For us, here in Fremont, the social costs of doing this liberative work has not been that high – at least not so far and at least not given how much of that liberative work we’ve done. This is not always the case.

Over the past month, our sibling United Church of Christ congregation in Loomis, California, has been facing increasing social costs. One of the ministries of this congregation is called “The Landing Spot.” The Landing Spot is a non-religious support group for LGBTQ+ youth and their parents. They are currently being targeted by far-right groups, some (and perhaps all) of which have ties to the White Christian Nationalist movement. The severity of the threats and harassment are increasing and the church sees them as part of “a coordinated attack on the LGBTQ community, [that of late is] specifically targeting transgender folks.”[4]

Their Church Council said in a public statement, “There is a wave of anti-LGBTQ violence and legislative attacks across the country and we are not immune.”[5] The Council also said, “As an immediate response to an influx of hateful and threatening messages, we will temporarily suspend in-person Loomis Basin UCC events on church property until church leadership can establish a plan to maintain the safety and security of our congregants. We believe this is the best way to protect our pastor and our congregants during this time of elevated attention for our local church.”[6]

I hope you will join me in praying for the Loomis Basin United Church of Christ, today and daily. With the help of a colleague, I have also drafted a simple letter of support to the Loomis Basin UCC that I invite you to sign during coffee hour.

I do not believe that, in the end, hateful, hate-filled people will have the final word. God is about reaching into the graves we dig for ourselves and that other dig for us, so that God can pull us out. And it happens all the time. Just look for the liberator and you’ll see God’s resurrection power at work. And if you want to be a co-conspirator in God’s resurrection, keep doing the liberative work of unbinding.

Amen.

[1] Elizabeth Schrader interview with Diana Butler Bass on 16 March 2023. Recorded and archived at https://dianabutlerbass.substack.com/p/libbie-schrader-preaching-john-11.

[2] Ibid.

[3] I’m quite sure this is in her book Pastrix: the Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner and Saint (New York: Jericho Books, 2013), though I’m not able to find it in there today.

[4] Statement from the Church Council on the website of Loomis Basin Congregational United Church of Christ, https://www.loomisucc.org/ (accessed 25 March 2023).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, April 3, 2022, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: John 12:1-8

Copyright © 2022 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

There is a version of the story of Jesus being anointed by a woman in each of the gospels. Each version is a little different.

- In Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the woman is unnamed. In John, it is Jesus’ friend Mary who anoints Jesus.

- In Matthew and Mark, the ointment is poured over Jesus’ head. In Luke and John, the ointment is poured on Jesus’ feet, which are then wiped with the woman’s hair.

- In Matthew and Mark, Jesus is in Bethany at the home of Simon the leper. In John, Jesus is in Bethany at the home of Lazarus, Martha, and Mary. In Luke, Jesus is, apparently, in the town of Nain at the home of an unnamed Pharisee.

- In Matthew, the disciples in general get upset about the cost of the ointment that was “wasted” by anointing Jesus. In Mark, it’s unclear who it is who gets upset about the cost of the ointment – disciples or others at the dinner. In Luke, no one gets upset about the cost of the ointment; it’s the supposed sinfulness of the unnamed woman that sends the other guests of the Pharisee into a tizzy. In John, it’s Judas the betrayer who says the money would have been better spent on the poor then on the ointment (apparently because he wanted to embezzle the money).

Our scripture lesson is from John’s gospel, so I really want to focus in on what John is saying. And recent scholarship is pointing out that, particularly when it comes to Mary and Martha in John’s gospel, that can be harder than one might think. A few years ago, Elizabeth Schrader, a PhD student at Duke University, noticed that some editing had happened to “Papyrus 66 – generally thought to be the oldest near-complete manuscript of the Gospel of John.…

“The word ‘Maria,’ (or Mary) had been altered, with the Greek iota symbol – the ‘i’ –scratched out and replaced with a ‘th’ that changed the name to ‘Martha.’ And in a later verse, a woman’s name was replaced with ‘the sisters.’

“This discovery was the first of many that Schrader … would make. She did so by poring over hundreds of transcriptions of these manuscripts that represent the work of so many scribes who hand-copied versions of the Bible; some of these scribes made slight changes along the way.

“The discovery, Schrader argues, points to a deliberate minimizing of the legacy of Mary Magdalene …”[1]

Schrader’s more recent work argues that “Magdalene may well be an honorific from the Hebrew and Aramaic roots for tower or magnified,”[2] rather than signifying what town she was from. Schrader says that, just as Jesus’ disciple Simon got the nickname Peter, the Rock, Mary might have acquired a title meaning tower of faith or Mary the magnified.[3]

Schrader is saying that the Mary in chapters 11 and 12 of John’s gospel, the Mary who is a sister to Lazarus, is Mary Magdalene, the Mary who, in John’s gospel, watched Jesus’ execution and burial, and who was the first witness to his resurrection, and that Martha is an invention added to the manuscripts later. I invite you to keep this in mind as we dig into today’s scripture lesson.

There’s a sentence that Jesus says in our lesson that is easily misinterpreted: “You always have the poor with you.” It is worthy of its own sermon. And I preached such a sermon at the beginning of February, so I refer you to it. Meanwhile, there’s plenty of other things going on in this story that are deserving of our attention.

Our reading is the beginning of chapter 12 in John’s gospel. However, I think we need to go back to chapter 11 to really see what’s going on there. Most of chapter 11 is devoted to telling the story of Lazarus’ death and resuscitation. There are two reactions to this most amazing of Jesus’ medical miracles. First, people in Bethany, friends of Mary’s family, start believing in Jesus. Second, people in power start plotting to kill Jesus – and Lazarus.

Just a few days later, we’re told at the beginning of chapter 12, Jesus returns to Bethany for dinner. At dinner, Mary takes a costly perfume and anoints Jesus’ feet with it, wiping them with her hair. The smell of the nard fills the house.

It’s not clear to me if nard was typically used for Jewish burials at the time of Jesus. As best I can tell, several different scents were used at different times. If nard was customarily used, I imagine the smell of the nard filling the house would have called to mind bodies that had been prepared for burial over the years. If not, I imagine the smell of the nard would have called to mind people putting on perfume, preparing themselves for celebrations. Either way, when Judas scolds Mary for using the expensive ointment on Jesus’ feet, he’s stealing memories as much as he’s wishing he could steal some money.

By the middle of chapter 12, Jesus enters Jerusalem with people waving palm branches and shouting his praises. And within a week of the dinner in Bethany, at the beginning of chapter 13, the disciples are gathered with Jesus for another dinner. This time, it’s Jesus who does the foot washing.

Death, Jesus’ impending death, is at the center of both suppers – the Bethany supper and the last supper. Jesus interprets Mary’s act as one of love and service in preparation for his death and burial. Then, at the Last Supper, Jesus calls his disciples to acts of love and service as he readies himself and the disciples for his crucifixion.

Jesus names the uncomfortable reality that is so easy to deny: we are all going to die. I know this is something we all know. We all know that we’re going to die. And yet we deny it. We all know we are fragile. These past two years have taught us that. These past two years have taught us to think about our fragility even to a microscopic virus. We know that we’re fragile. And yet we deny it. Maybe one of the things this scripture can teach us is the value of talking about our own mortality.

This is not unique to this story. In their own ways, the Jesus in each of the gospels foretells of his death – and the disciples never seem to accept it. There’s a wonderful scene in Matthew’s gospel where Peter declares that Jesus is “the Messiah, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16). Jesus commends Peter and then starts to explain what being the Messiah means – that he’ll “undergo great suffering” at the hands of the elites and be killed. And Peter will have none of it. Peter has just said that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of the living God, and then tells Jesus that Jesus doesn’t know what he’s talking about when it comes to his death. Peter has become Cleopatra, the Queen of Denial.

It is the unusual person who is willing to talk about their death. I know people (including people who have children) who refuse to make a will or do any estate planning because to do so would be to admit that they will, someday, die. And yet, it’s going to happen. We are fragile. All of us are going to die. And poor Lazarus had to do it twice.

We don’t know if Mary was able to step past her own denial about death. We know that Jesus interprets her anointing his feet with nard as an act of burial preparation, but we don’t know if that was Mary’s motivation.

John’s original may be more radical that what we have now. If Schrader is right, that the Mary in John 11 and 12 is Mary Magdalene, and that Martha is a later invention/insertion, then it is Mary who confesses that Jesus is the Messiah in chapter 11 (not Martha), and what Mary may be doing is the very thing that Messiah means – anointed one. Mary may be anointing Jesus king.[4]

This is a radical and new enough idea that I’m still wrapping my head around it. I’ll probably write some more about it in my Wednesday “A Pastoral Word” email. (If you’re not signed up for that email, you can sign up for it and other email lists via a link on the front page of the church’s website.)

In the meantime, consider this possible motivation: Maybe Mary was simply acting out of her sense of love and respect – perhaps even overwhelming gratitude – for Jesus. Her rabbi was at her home for dinner, her rabbi who had just resuscitated her brother after he’d been dead for days. Maybe she simply wanted to express her gratitude.

Or maybe she knew that resuscitating Lazarus would get Jesus in trouble with the powerful. Maybe she knew that the principalities and powers would be out to get Jesus and she didn’t want to wait to express what she felt. Maybe she felt she had to live that day as if it was Jesus’ last – or her last – because it just might be. Maybe Mary knew that we are fragile and so it was a good day to celebrate life.

We don’t know what her motivation was. Nonetheless, I see in her actions an invitation to live, even in the midst of death.

We are fragile. We are all going to die. So why not live now? Don’t wait until you’ve got your life squared away and looking perfect. Your life is good enough now, right now, for living.

Amen.

[1] Eric Ferreri, “Mary or Martha? A Duke Scholar’s Research Finds Mary Magdalene Downplayed by New Testament Scribes,” Duke Today, https://today.duke.edu/2019/06/mary-or-martha-duke-scholars-research-finds-mary-magdalene-downplayed-new-testament-scribes (posted 18 June 2019; accessed 3 April 2022).

[2] Yonat Shimron, Religious News Service, quoted in “Was Mary Magdalene really from Magdala? Two scholars examine the evidence,” Christian Century, 9 February 2022 edition, p. 16.

[3] Ibid.

[4] This is the contention of Diana Butler Bass in her email “The Cottage,” emailed this morning (3 April 2022) at 1:31 a.m. I haven’t fully digested it.

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, December 19, 2021, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: Luke 1:46-55

Copyright © 2021 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

When you think of “a room with a view,” what comes to mind? What images does that phrase evoke? I think of expensive apartments overlooking New York City’s Central Park, or condos perched under the Sutro Tower in San Francisco that look across the city onto the Bay Bridge. I think of hotel rooms on island resorts that look over the ocean or cabins with decks that look across a lake and into the mountains. When I hear someone talking about “a room with a view,” I think about beauty and calm and nature and expense.

I also think about an old joke about the first test tube babies. Psychologists were worried that they would grow up to be quite full of themselves because their conceptions took place in a womb with a view.

As I reflected on the theme for today’s sermon, I realized that every room has a view. Even if there are no windows in that room, the view may be out the door and down the hall. Every room has a view. When I arrived on campus for my freshman year of college, I was directed to my dorm room. It was on the ground floor, and because of the slope of the ground around the building, the bottom of my room’s windows were only a few inches above the grass. I stepped into the room with its cold, cinder block walls, a bunk bed on one side with bare mattresses on it. I looked out the window across maybe 10 feet of grass to the wrought iron fence that encircled the campus, its cold black vertical bars separating the campus from the rest of the city. A room with a view that made me wonder when I could see the warden.

Every room has a view, and I’ve been wondering, what view Mary had from her room growing up. I’ve been wondering what she saw as a child and as a young, betrothed woman. When I listen to her song, I imagine that she saw the socio-economic realities of her world quite clearly. Mary’s view saw a distant elite, an occupying army, and a vast number of people who were barely surviving from day to day.

The song lyrics we heard in today’s reading are from a song Mary sang during a visit with her cousin Elizabeth, who was also pregnant with a child who would become John the Baptist. This song is Mary’s prophecy. This song echoes the song Miriam sang when the Hebrews, escaping slavery in Egypt centuries earlier, crossed the Red Sea.

In a recent interview, theologian John Berquist notes (pun intended), “there’s something about the voice that is singing, that even if you’re not close enough to see the singer, even if you’re not close enough to hear the words, it is still compelling and makes you want to seek out what is happening and to feel with it. And this is a song of such a vulnerability and of such joy that it’s [a] moving experience. And she is singing this with Jesus in the womb. These melodies of God working among the lowly is what Jesus first learns to dance to.”[1]

Berquist isn’t the first to suggest that Mary had a profound influence on Jesus, that her worldview was important to the worldview Jesus went on to develop. Paintings from the European Renaissance sometimes depict Mary studying when the Angel Gabriel came to tell her she was going to have a special baby, or sometimes depict a toddler Jesus on her lap as she studies. She must have known her theology to teach it to her child, the artists seem to say. A noteworthy problem with these pictures is that they depict Mary as a member of the elite and as someone who is literate. The historical Mary was almost certainly from the peasant to class and illiterate.

While I think that Mary certainly taught Jesus, I think she taught from the view she had from her room. My understanding of what that means is very much more like the understanding of the Mennonite pastor Isaac Villegas than of the Renaissance painters:

“Jesus must have learned his prophetic ministry from his mother. She was the one who said, ‘The Lord has brought down the powerful from their thrones, and lifted up the lowly; God has filled the hungry with good things, and sent the rich away empty’ (Luke 1:52–53).

“Jesus learned this gospel when he was a child, a baby, as he fussed at his bedtime. He learned his message from Mary, as she held him in her arms, rocking him, whispering her song, comforting him with dreams of a new world—the Magnificat as a lullaby. Mary preached with a song of joy. Political power is about who has a voice, who can speak, who we listen to. And here, at the beginning of Luke’s Gospel, the voice we hear is Mary’s.

“‘Truly,’ she says with authority, ‘from now on all generations will call me blessed’ (1:48). She knows who she is; she knows what God has done, not just for her but for all of us through her. It will mean a transformation of the world, a structural overhaul of society. The powerful will be brought down from their thrones and the lowly lifted up.

“Mary prophesies a new political arrangement, which will involve the abolition of the old systems of power. This revolution springs from the advent of ‘God’s mercy … from generation to generation’ (1:50). She sings her song ‘in remembrance of God’s mercy’ (1:54), which shatters the institutions of injustice that threaten and imprison. Mercy will melt the iron grip of oppressors. Mercy means her liberation and ours.”[2]

Songs like Mary’s can be very powerful teaching tools. You may recall that during Advent, we’ve been singing Christmas carols that have a verse that has been forgotten or ignored, left out of most contemporary hymnals. Today’s carol is “O Come, All Ye Faithful.”

Today, we sing a 19th century version of this hymn, which was originally written in the middle of the 18th century, in Latin, by the English composer John Francis Wade for a Catholic community. Three verses were added to Wade’s original four verses around 1822, and an eighth was added a few decades later. In the middle of the 19th century, some of the verses were translated into English.[3] Eventually all eight verses were translated, though today, few hymnals have more than four of the eight verses—at least among Protestant hymnals. Verse two is often left out, a verse that draws heavily from the Nicene Creed. The eighth verse is about the Magi and is typically left out, too. However, the often left-out verse that I want to focus on is the fifth verse.

This fifth verse connects with Mary’s song in several ways, most importantly because it reminds us both of our humility (our lowliness) and of how deeply loved we are. While we may, in many ways, be the powerful that Mary sings will be brought low, we are also, in many ways, lowly and in need of healing. Take a look at the lyrics of the fifth verse:

Child, for us sinners

poor and in the manger,

Fain we embrace thee, with awe and love:

Who would not love thee,

loving us so dearly?

O come, let us adore him …

Professor of Sacred Music C. Michael Hawn notes, “The fifth stanza takes a decidedly different tone, placing us not only at the manger scene as one of the humble who have come to see the Christ child, but actually in the manger! Note that there is no comma after ‘sinners,’ indicating that it is not just the ‘Child’ in the manger, but we who join him there in humility, ‘awe and love’.” Then Hawn suggests, “the rhetorical question leaves us almost unable to sing the refrain aloud.”[4] “Who would not love thee, loving us so dearly?”

Perhaps we can hear in Mary’s song the invitation to do some soul searching, to figure out where we fit in the cosmic order of God’s reign. Perhaps we can let Mary’s hopeful and convicting words draw us deeper into an appreciation for and an acceptance of God’s grace. It is only by God’s grace that I think Mary was able to sing these words of hope and transformation in the face of the reality she saw when she viewed the world from her room. And in that grace, Mary learned to view the world as God does: through the eyes of love.

“Love redeems,” wrote the late bell hooks. “Despite all the lovelessness that surrounds us, nothing has been able to block our longing for love, the intensity of our yearning. The understanding that love redeems appears to be a resilient aspect of the heart’s knowledge. The healing power of redemptive love lures us and calls us towards the possibility of healing. Like all great mysteries, we are all mysteriously called to love no matter the conditions of our lives, the degree of our depravity or despair. The persistence of this call gives us reason to hope. Without hope, we cannot return to love.”[5]

Regardless of where our rooms are and what they look out upon, let us learn to view the world as God does, with eyes of grace-filled love. In doing so, I believe we will make room for the holy. Amen.

[1] John Berquist, in an interview with Marcia McFee, Worship Design Studio, www.worshipdesignstudio.com,

[2] Isaac S. Villegas, “The politics of Mary,” Christian Century, 2 December 2020, p. 37.

[3] “Adeste, Fideles,” Hymns and Carols of Christmas, https://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Hymns_and_Carols/NonEnglish/adeste_fideles.htm (accessed 18 December 2021).

[4] C. Michael Hawn, “History of Hymns: ‘O Come, All Ye Faithful,” Discipleship Ministries, UMC, https://www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/history-of-hymns-o-come-all-ye-faithful (posted 20 May 2013; accessed 8 December 2021).

[5] bell hooks, All About Love: New Visions, quoted by Ibram X. Kendi on Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/ibramxkendi/posts/460197198797980 (posted and accessed 15 December 2021).

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, December 13, 2020, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scripture: Luke 1:46-55

Copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

I like how my colleague, Bruce Epperly, says it: “The calling of Mary is as much about divine revelation as obstetrics.”[1] To be honest, I think that every birth – and not only human births – every birth is a miracle. That the stem cells that become skin cells end up on the outside of animals (including humans) is, in my book, a miracle. And in terms of our spiritual journeys, yours and mine, there is a miracle in this story of far greater importance than Mary’s pregnancy. That is the miracle of her “yes” to God.

Luke’s “nativity story begins with a surprising angelic visit to an ordinary young woman, perhaps 13-16 years of age, [based on her being] on the verge of marriage. There is no hint that she is sinless or immune from the vicissitudes of human life. There is nothing in the gospel account that would point to her uniqueness metaphysically or prenatally.… She was the child of mortals who shared in the challenges and ambiguities of mortality.”[2] In fact, I find seeing her as an “everywoman” to be a much richer and more challenging view than seeing Mary as a sinless immortal. She could be my sister or my niece or any one of us being “called by God, in challenging times, to give birth to God’s new age.”[3]

Luke tells us that soon after she found out she was pregnant, she went to visit her much older cousin Elizabeth (who was also surprisingly pregnant). It is during that visit to Elizabeth that Mary breaks into song, the lyrics of which we heard in our scripture reading today. She offers a hymn of praise that we’ve come to know by the first word of the song in Latin, the Magnificat.

In this song, Mary “proclaims her humility and God’s greatness and then launches out into a world-changing message. God’s coming rule, alive in the child she will bear, turns everything upside down. Unjust social structures are overturned – the hungry are fed, the wealthy sacrifice, tax policies benefit the poor, leaders seek peace, and schools are safe; roles are reversed as God’s peaceable realm comes to earth. This is the way life is meant to be when God’s realm is ‘on earth as it is in heaven.’ This is the calling of Jesus’ followers, especially in this time of pandemic which has starkly revealed the economic and racial injustice of the USA and has put millions at risk across the globe.”[4]

I asked the participants in Monday’s Bible Study who come to mind as they heard Mary’s hymn of praise. Jeff Bazos and Elon Musk and the other U.S. billionaires are who came to my mind. And later in the week, this tweet from Robert Reich reaffirmed that our nation is drifting away from the vision on Mary’s song.

These were not the people that came to mind for the Bible Study participants. They thought about:

- The women who first come forward to report the sexual abuse by a longtime USA Gymnastics national team doctor.

- Students like Emma González, who have worked so hard to stop gun violence.

- Greta Thunberg and so many other young climate activists.

- Malala Yousafzai

- The women[5] who started Black Lives Matter

I love that powerful, young woman came to mind, that people who are changing the world came to mind, and not the rulers who need to be taken down from their thrones. And after being truly moved by this list this week, I’m adding Autumn Peltier and all the Native young people who have worked and continue to work as water protectors across North America.

It seems to me that the characteristic that all of these women and girls have in common in bravery. Courageous acts, brave acts are not those what are carried out without fear. They are the acts that are carried out despite the fear. In the Bible, when angels appear to people, they almost always start by saying, “Fear not,” or “Do not be afraid.” I think that what they mean is “Be brave.” And that call – to be brave – is a call to be vulnerable.

Now, being vulnerable is hard. Brené Brown points out, “Vulnerability is the ‘gooey center’ of hard emotions like shame, scarcity, fear, anxiety, uncertainty.”[6] Who wants to be feeling those emotions? I don’t like feeling shame; I don’t like feeling like I’m not worthy of real connection. I don’t like feeling like there isn’t enough. I don’t like being afraid or anxious or uncertain. I want (to use Brown’s term) to “armor up.” I want to guard against these hard emotions and if I can’t guard against them, I certainly don’t want to be seen having them. However, if I guard against them, I guard against all vulnerability. And “vulnerability is also the birthplace of love, belonging, and joy.”[7] And do I want to experience love, belonging, and joy.

Brown says some really interesting and deep things about the vulnerability of love and belonging. But joy – “joy is the most vulnerable of all human emotions. We are terrified to feel joy. We are so afraid that if we let ourselves feel joy something will come along and rip it away from us and we will get sucker punched by pain and trauma and loss. That [is why,] in the midst of great things, we dress rehearse tragedy. [Those of you who are] parents,… have you ever stood over your child while they’re sleeping and thought, ‘I love you like I didn’t know was possible,’ and then in that split second you picture something horrific happening to your child? [Or how about this, if you never had children or your children are grown.] … You wake up you’re feeling pretty good: things are good, your family’s good, the house is good, and suddenly you’re thinking, ‘Holy ****’ and you’re waiting for the other shoe to drop.

“… When we lose our capacity for vulnerability, joy becomes foreboding. It becomes scary to let ourselves feel it. The research participants [Brown studies] who had the ability to lean fully into joy only share one variable in common. They only share one thing across all the variables.… The one thing they share is gratitude – they practice gratitude.… Vulnerability has a real physiology. Our body [have a physiological reaction to vulnerability]. Some people use that as a warning to start dress rehearsing for bad things. Some of us try to use it as a reminder to be grateful.

“[Which can be hard, because] gratitude is also vulnerable.… Sometimes we’re afraid to feel gratitude because we feel like it is dangerous to say ‘I’m grateful’ for something because it is like someone listening take it away. My God doesn’t work that way, [and even though I believe that,] sometimes I fear God might [it] anyway.…”[8]

So, Brown suggests, “just do the joyful thing for the hell of it. Just choose joy sometimes. Just choose a thing that seems frivolous and fun and has no return-on-investment or payoff or upside. Just do the joyful thing you know.”[9]

If Brené Brown is right (and I think she is), that “joy is the most vulnerable of all human emotions,” I wonder if there’s a correlation for the opposite direction. It seems that joy can come or be chosen in the most vulnerable and hopeless of situations.

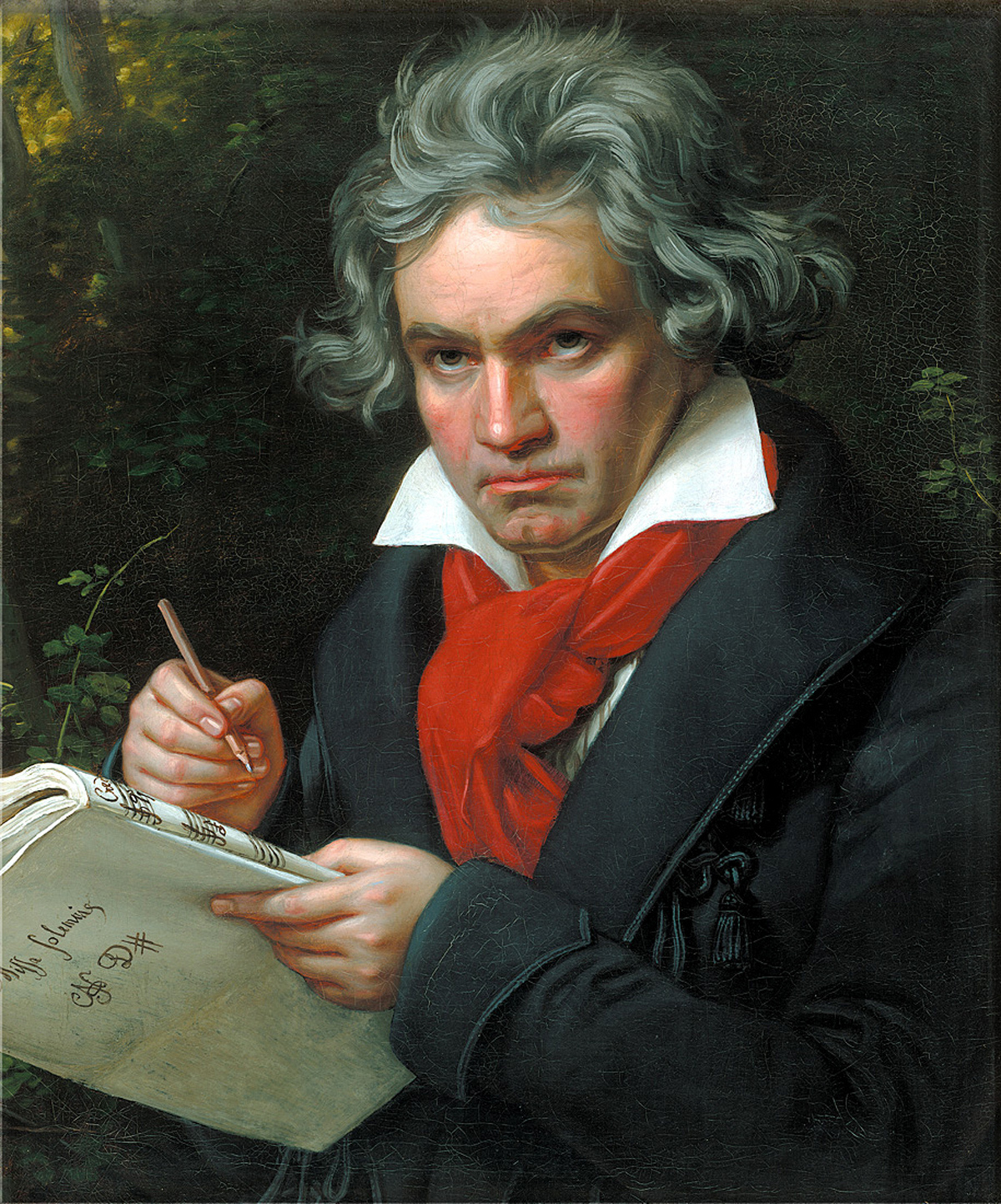

Consider Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. Beethoven wrote it when he was deaf. That means he never heard an orchestra and chorus perform it. And he knew he never would hear it as he was writing it. Sick, alienated from almost everyone, Beethoven nevertheless created an anthem of joy that embraces the transcendence of beauty over suffering. It has become an anthem of liberation and hope around the world.

It is the piece the students in Tiananmen Square played over their loudspeakers in 1989 as the army came to crush their struggle for freedom. Women in Chile, living under the Pinochet dictatorship, sang the Ninth at torture prisons, where men inside took hope when they heard their voices. The Berlin Wall collapsed to the sound of the Ninth. In Japan each December, the Ninth is performed hundreds of times, often with 10,000 people in the chorus, a tradition that gave the survivors of the 2011 earthquake and tsunami strength and hope.[10]

The entire fourth moment of the symphony is about joy, and to sing about joy in these vulnerable situations seems so counterintuitive. Sort of like an unwed, pregnant teenager singing about God doing great things for her.

As Epperly points out, “Mary’s willingness to say ‘yes’ and then act upon her affirmation inspires us to be agents in God’s adventure. God presents possibilities for new birth and we are called to carry these possibilities to term and nurture them in our rough and tumble world.”[11] And in the process, we might find a deep joy that transforms us and the world.

Amen.

Questions for Reflection:

- What societal changes do you think are needed for God’s realm to be “on earth as it is in heaven”?

- Who are your “contemporary brave souls”?

- How well do you lean into joy?

How can you get better at leaning into joy? - What “yes” can you say to God today?

[1] Bruce Epperly, “The Adventurous Lectionary – the Fourth Sunday of Advent, December 20, 2020,” Patheos, https://www.patheos.com/blogs/livingaholyadventure/2020/12/the-adventurous-lectionary-the-fourth-sunday-of-advent-december-20-2020/ (posted and accessed 10 December 2020).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi.

[6] Brené Brown, “The Call to Courage,” a Netflix special. The quotes are not exact – both because of my transcription skills (or lack thereof) and because some editing makes it easier to understand.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] From the website for the documentary Following the Ninth, https://www.followingtheninth.com/about-the-film.html (accessed 12 December 2020).

[11] Epperly, op. cit.

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, January 5, 2020, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scriptures: Luke 2:22-38 and Exodus 13:11-16

Copyright © 2020 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

“When [the shepherds] saw [exactly what the angels had told them they would find], they made known what had been told them about this child; and all who heard it were amazed at what the shepherds told them. But Mary treasured all these words and pondered them in her heart. The shepherds returned, glorifying and praising God for all they had heard and seen, as it had been told them.”

When we hear these verses from the second chapter of Luke’s gospel, we think we’ve heard the end of the Christmas story. If you’re like me, you imagine granddad closing the book he’s been reading out of. It’s a sweet ending to a sweet story – Mary pondering what she’s heard and the shepherds returning to the hills and their flocks praising and glorifying God.

Except it’s not the end of the story. It’s only the beginning of the beginning of the story. Giving birth to a baby is always only the beginning. In some ways, it’s the easy part. The poet Kaitlin Hardy Shetler reflected:

Except it’s not the end of the story. It’s only the beginning of the beginning of the story. Giving birth to a baby is always only the beginning. In some ways, it’s the easy part. The poet Kaitlin Hardy Shetler reflected:

Sometimes I wonder

if Mary breastfed Jesus.

if she cried out when he bit her

or if she sobbed when he would not latch.[1]

As good Jews (and Luke makes a big point of showing that Mary and Joseph were good Jews), there were religious obligations to fulfill, in addition to worrying about breastfeeding and diaper cleaning. When he was eight days old, they had to have the baby circumcised. This was also when Jesus was officially named – the name given by the angel before he was conceived. And there was a purification obligation. And there was the obligation to offer a sacrifice in place of the first-born son.

Luke sort of mushes these last two obligations together. Mary, not both parents, needed to undergo a rite of purification after giving birth (see Leviticus 12:2-8). And then the parents needed to present a sacrificial offering in lieu of a first-born child, because the first-born child belongs “to the Lord,” as we heard in our second lesson from Exodus.[2]

Don’t gloss over the part about Jesus’ parents offering two birds as the sacrifice. This places them in the ranks of the poor. Had they had wealth, they would have presented a lamb. This echoes a theme earlier in Luke’s gospel, when Mary sings of her solidarity with the poor, a solidary she shares with God.[3]

It’s pretty clear that one of Luke’s points is that this family is Jewish, that they are good Jews who follow the law of Moses. The fulfilling of the law also serves a narrative purpose. The story of the presentation at the Temple gets the Holy Family onto the Temple grounds. That’s where Mary, Joseph, and their new-born had to go to make their sacrifice. That, in itself, isn’t unusual. Like thousands of other families that year, Mary and Joseph presented their first-born child at the Temple and offered their sacrifice. But this is no ordinary family, and their baby is no ordinary child.

I imagine Simeon and Anna coming to the Temple, week after week, month after month, year after year, and looking at all the babies brought to the Temple. Temple regulars were probably used to these two elderly people oo-ing and ah-ing over babies, but never seeming to be fully satisfied with what they saw. This time, something was different. This time, when they looked at the baby, they knew that they are in a kairos moment, they are at a turning point. Everything was changing.

The Greek has two words for talking about time. There’s chronos, the word from which we get “chronology.” This is linear time. This is measurable time. This is time on a straight timeline. And then there’s kairos. This is time that is full, that is pregnant with possibilities. This is where – or when – time bends.

Simeon took the baby in his arms declared that he could now die in peace, for he has seen God’s salvation. The theologian William Greenway points out that Simeon doesn’t declare that he can die in peace because he believes that he will live again after death. He doesn’t say that he can die in peace because he is sure that Jesus will bring a sociopolitical revolution. The salvation Simeon sees is actually about living – “living in the light of the love of God for one’s own and for every other Face, living in the light of a power greater even than our fear of death, living in koinonia, [in a deep, life-giving fellowship], living in the communion of shalom.”[4]

Theologian John Carroll says, “Simeon’s prayer-oracle blends grateful praise and bold prophecy. He affirms the fulfillment of Israel’s long-deferred hopes of divine deliverance; this is the reasons for a people’s consolation, as well as for his personal sense of ‘release’ to a death in peace. He also expands the scope of the blessing to encompass all nations, in the spirit of … [the prophet] Isaiah.”[5]

And then there’s Anna. I wish Luke told us more about Anna. It is worth noting that Luke calls her a “prophet.” That is an important title, especially for a woman. I just wish Luke told us more about what she said. Instead, all we learn is that Anna, the first to tell the good news of Jesus in Luke’s gospel, starts telling the people who have been waiting for the redemption of Israel all about the child.

And then there’s Anna. I wish Luke told us more about Anna. It is worth noting that Luke calls her a “prophet.” That is an important title, especially for a woman. I just wish Luke told us more about what she said. Instead, all we learn is that Anna, the first to tell the good news of Jesus in Luke’s gospel, starts telling the people who have been waiting for the redemption of Israel all about the child.

One of the things I’ve noticed about the nativity stories – both Luke’s and Matthew’s – is that they are full of mystics.[6] The stereotype many of us carry sees mystics as people who have the experience on ecstatic union with the divine, and that this type of experience is reserved for a few rarefied saints. I, however, prefer Ruth Haley Barton’s view of what a mystic is. “[M]ystics are those who really believe what the rest of us say we believe – that God is real, that God is mystery (that is, totally beyond our human comprehension), that God can be encountered in the depths of our being, and that our human lives can be radically oriented and responsive to the One who is always present with us.

“Mystics are those who are open to actual encounters with God that are often unmediated by religious trappings. These encounters are often given to those who find themselves on the fringes of institutional religious structures while remaining radically committed to what is truest about our faith. Mystics are those who have a longing for God that is so profound that they make radical choices to seek God and respond to God’s leading in their lives.”[7]

Think about the principle players in the nativity stories (except for Herod). By this definition, they’re all mystics. In Matthew’s gospel, there’s Joseph who pays attention to the divine presences in his dreams. And there are magi who were paying attention to the signs in the heavens in such a way that the signs drew them to Jerusalem. And these same magi paid attention to their dreams in a way that sent them home by another way.

In Luke’s gospel, we have Zechariah who encounters an angel in the holiest spot in the Temple. And Mary who listens to the angel’s invitation. And Elizabeth, her cousin, who senses the holiness of the moment when Mary comes for a visit. And shepherds who go investigate what the angel proclaimed. And then there are Simeon and Anna, elders (with all the wisdom that title confers), who saw in Jesus the salvation of the world.

The mischievous part of me imagines, after Simeon offered his blessing-oracle and Anna finished prophesying about Jesus (for the morning, at least), that the two of them got together and said to each other, almost simultaneously, “That was worth waiting for.” And then I start to wonder, what made them keep coming back to the Temple, day after day? What empowered their faithfulness, their trust, that they would live to that kairos moment when they, in their wisdom, could see the world changing?

I have found the first four days of 2020 to be emotionally and spiritually difficult. The disastrous fires and scorching heat across the entire continent of Australia have, in the past three months, released as much carbon into the atmosphere as the entire country produces from every car, home, and factory in a typical eight-month period.[8] As Bill McKibben puts it, “Climate chaos feeds on itself now.”[9]

I have found the first four days of 2020 to be emotionally and spiritually difficult. The disastrous fires and scorching heat across the entire continent of Australia have, in the past three months, released as much carbon into the atmosphere as the entire country produces from every car, home, and factory in a typical eight-month period.[8] As Bill McKibben puts it, “Climate chaos feeds on itself now.”[9]

Meanwhile, because of what were described by officials as “not ordinary rains”[10] (though extraordinary weather is the new climate chaos norm), the flooding and mudslides in and around Jakarta has led to over 50 deaths and around 400,000 people displaced.[11]

And as if that wasn’t bad enough, the United States moved closer war with Iran by killing Iranian General Soleimani on Thursday.

Like I said, the first four days of 2020 were emotionally and spiritually difficult.

I like to start the new year with the hope that comes from a vision of what could be. I like to start the new year thinking about the things that I want to see happen in my lifetime and plotting how to help make them happen. I would love to see sufficient global action to mitigate the impacts of climate change. I would love to see the growth of equality – all kinds of equality – within the United States and around the world. I would love to see the rise of political leaders who embrace and act on a vision of peace that is grounded in justice and mutual respect. I would love to see these things happen in my lifetime, and if I did, I think I would depart in peace.

But right now, all these things I want to see seem so far away. That’s why, today, what I would like is to be a little more of a mystic. Today, I would simply like to be more attentive to the presence of God with us. Today, I would like to have the spiritual stamina of Anna and Simeon.

How about you?

_______________

Questions for contemplation:

What would you like to see happen in your lifetime?

What spiritual practice could you embrace that might help you to be more of a mystic?

_______________

[1] This is the first stanza of an unnamed poem attributed to Kaitlin Hardy Shetler, posted by Traci Blackmon, Facebook, https://www.facebook.com/traci.blackmon/posts/10219831021187339, (posted and accessed 18 December 2019).

[2] John T. Carroll, “Luke 2:21-24: Exegetical Perspective,” Feasting on the Gospels: Luke, Volume 1 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 47.

[3] Ibid, 49.

[4] William Greenway, “Luke 2:25-40: Theological Perspective,” Feasting on the Gospels: Luke, Volume 1 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2014), 52.

[5] John T. Carroll, op. cit., 53.

[6] I am indebted to Ruth Haley Barton, “Epiphany: A Dangerous Journey,” Transforming Center, https://transformingcenter.org/2020/01/epiphany-a-dangerous-journey/ (posted 2 January 2020; accessed 3 January 2020), for this insight.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Mike Foley, “Bushfires spew two-thirds of national carbon emissions in one season,” The Sydney Morning Herald, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/bushfires-spew-two-thirds-of-national-carbon-emissions-in-one-season-20200102-p53oez.html (posted 2 January 2020; accessed 3 January 2020).

[9] Bill McKibben, Twitter post https://twitter.com/billmckibben/status/1213095386887475200 (posted and accessed 3 January 2020).

[10] “Jakarta floods: ‘Not ordinary rain’, say officials,” BBC News, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-50969418 (posted and accessed 2 January 2020).

[11] Rashaan Ayesh, “Death toll rises in Indonesia flooding landslides and flooding,” Axios, https://www.axios.com/death-indonesia-landslides-flooding-426cccbd-3dfe-4aee-9ec8-1d3eda35352f.html (posted and accessed 4 January 2020).

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, December 8, 2019, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scriptures: Luke 1:5-20 and Luke 1:26-38

Copyright © 2019 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

Some 25 years ago, I was driving a borrowed pick-up truck towing a borrowed motorboat. I’d spent the week on Lake Coeur d’Alene at the United Church of Christ camp along the lake’s eastern shore with a big group of youth. I was driving back to Richland, Washington, and I was about halfway between Ritzville and Pasco, so about 50 miles from the anywhere, when the trailer started swaying behind me. As I slowed down, it kept swaying, so I nursed the truck to a stop on the shoulder of highway 395.

I went back to see what was going on. The tongue of the trailer had lifted the ball of the hitch out of the bumper and was resting in the chain cradle I had made when I dutifully attached the trailer to the truck. The nut attaching the ball to the bumper had come off somewhere in the last 100 or so miles.

I went back to see what was going on. The tongue of the trailer had lifted the ball of the hitch out of the bumper and was resting in the chain cradle I had made when I dutifully attached the trailer to the truck. The nut attaching the ball to the bumper had come off somewhere in the last 100 or so miles.

I had no idea what to do.

This was in the days before cell phones, so I sat in the cab of the truck feeling quite helpless as the sun started to set. I was lost in my own thoughts and fears when there was a knock on the passenger door. Startled, I looked up and there was a guy who worked for the railroad pulled off the highway onto the shoulder checking in on me. The next thing I knew, there were three railroad service trucks pulled off onto this significant shoulder, and these guys (with more mechanical aptitude than I have) were busy trying to figure out how to fix the problem.

That was the first amazing thing to happen. The second amazing thing to happen was that one of them found a nut that fit the threads of the ball. The third amazing thing to happen was that I had a wrench that fit the nut that fit the ball that was supposed to be attached to the bumper.

We got it fixed. And all but one of the trucks disappeared. And the guy who had tapped on the passenger door said he’d follow me the 50 miles to Pasco just to make sure nothing else went wrong. And after Pasco, I only had another dozen miles to go to get home.

Now, you can tell me that these guys were just railroad employees on their way home helping out a helpless guy. But it sure felt to me like it was one miracle after another that evening, and I kind of expected wings to pop out of their shoulders.

I have preached on today’s scripture lessons before. I’ve preached on the Zechariah scripture several times. I’ve preached on the Mary scripture (the Annunciation, it’s called) many times. I’ve preached about Zechariah. I’ve preached about Elizabeth. I’ve preached about Mary. I’ve preached about Joseph. I have never preached about Gabriel. Sure, I’ve mentioned Gabriel. It’s hard to talk about God inviting Mary to make room in her life and in her body for Jesus without mentioning the messenger who brought that invitation. Gabriel is a character in both of these scriptures, and I’ve never looked at either story from Gabriel’s point of view.

As I pondered why that is this week, I realized that I don’t really have a theology of angels. I’ve treated angels in the Bible as literary devices employed to move the narrative along. The author can have a storm kick up, or a beggar yell out, or a soldier harass people to move the story along. In the same way, the author can have an angel show up and push the story in a new direction. We saw this at work last week when we looked at Joseph’s dreams. An angel (unnamed) shows up in his dreams to communicate some divine direction or to give some divine advice. The angel isn’t important. It’s the message the angel brings that is important. The angel is just a device to communicate the message.

Or at least that’s how I’ve looked at them.

I found myself wondering this week, “Why did Luke tell us the name of the angel in these two stories?” I started my quest to answer my question by learning something about the general view of angels in first century Judaism. What I’ve learned so far is interesting, but I still have a lot of questions.

References to angels appear in some of the earliest stories in the Hebrew scriptures. We read about three strangers showing up at Abraham and Sarah’s tent telling them that (despite their advance years) they’re going to have a baby. These strangers are presumably angels, for they share things only God could know. Later, we read about an angel stopping Abraham when he is about to sacrifice Isaac. We read about Jacob dreaming about angels ascending to the heavens and descending from the heavens. There are references to angels in other places in the Torah (the first five books of the Bible), in the prophets, and in the wisdom literature.

References to angels appear in some of the earliest stories in the Hebrew scriptures. We read about three strangers showing up at Abraham and Sarah’s tent telling them that (despite their advance years) they’re going to have a baby. These strangers are presumably angels, for they share things only God could know. Later, we read about an angel stopping Abraham when he is about to sacrifice Isaac. We read about Jacob dreaming about angels ascending to the heavens and descending from the heavens. There are references to angels in other places in the Torah (the first five books of the Bible), in the prophets, and in the wisdom literature.

The Hebrew word for angel is “malach,” which means messenger. So it makes sense to think of angels primarily as God’s messengers.[1] And that is certainly the role we see Gabriel playing in today’s readings. Yet, according to Jewish tradition, angels do more than deliver God’s telegrams. For instance, various of the Archangels had (and presumably still have) special jobs. Michael takes care of missions that are expressions of God’s kindness. Gabriel executes God’s judgments. Rafael is responsible for carrying out God’s healing. Or, in some cases, these archangels are responsible for organizing other angels in carrying out these tasks.[2]

My problem is that I don’t know when this degree of angelic specificity developed. Certainly by the middle ages, the rabbinic tradition had developed a whole angelic hierarchy with ten ranks of angels, each rank of angels having a greater or lesser understanding of God.[3] However, I don’t think that this detail of belief had yet developed by the time of Jesus. In fact, it is interesting to note that in the early writing of the Bible, angels often refused to share their names. It is almost as if the mystery surrounding angels is important. We don’t hear an angel’s name until the book of Daniel, which might have been written as early as the sixth century BCE, but might be from much later in the second century BCE.[4] Oh, and the angels named in the book of Daniel were Michael and Gabriel.

The only other place in the Bible where Gabriel shows up by name is in the two readings we heard today. I had thought for sure Gabriel is the angel who tells the shepherds to go to Bethlehem to seek the baby wrapped in swaddling cloth. Nope. It is “an angel of the Lord,” but the angel isn’t named.

There is a character in Ezekiel who is traditionally interpreted to be Gabriel, but he is not specifically named. He is simply “a man in linen” (see Ezekiel 9).

Written probably around the same time as Luke’s gospel, there is a Jewish book called Enoch. Jews do not consider it to be scripture, yet it is informative. Among other things, the book talks about the origins of demons and it talks about angels. This is the book in which Gabriel gets identified as an archangel. The archangels are the ‘angels of the presence’ who stand before God’s throne praising God and interceding for people.[5]

We hear this identity echoed in Luke when Gabriel explains who he is to Zechariah: “I am Gabriel. I stand in the presence of God, and I have been sent to speak to you and to bring you this good news.” It is possible that Luke identifies the angel who appears to Zechariah and Mary as Gabriel to emphasize that the messages Gabriel brings are directly from God. You can’t get a better source for direction from God than an archangel.

There is a Christian tradition that connects Gabriel to the end of time. There are several verses in various New Testament books that refer to a sounding blast or a trumpet blast that will be heard when time comes to an end and Jesus returns. Somewhere along the line, Gabriel ended up being the trumpeter. I because familiar with this idea of Gabriel as the trumpeter through Cole Porter’s Anything Goes and the song “Blow, Gabriel, Blow.” Cole Porter got the idea from the 1930 play The Green Pastures, which was based on spirituals. It’s not clear where the African American spirituals got the idea, though it’s likely from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Before that, there’s a 15th century Armenian manuscript illumination of Gabriel with a trumpet. And before that, in 1382, John Wycliff identified Gabriel as the trumpeter in a religious tract he wrote.[6]

There is a Christian tradition that connects Gabriel to the end of time. There are several verses in various New Testament books that refer to a sounding blast or a trumpet blast that will be heard when time comes to an end and Jesus returns. Somewhere along the line, Gabriel ended up being the trumpeter. I because familiar with this idea of Gabriel as the trumpeter through Cole Porter’s Anything Goes and the song “Blow, Gabriel, Blow.” Cole Porter got the idea from the 1930 play The Green Pastures, which was based on spirituals. It’s not clear where the African American spirituals got the idea, though it’s likely from John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Before that, there’s a 15th century Armenian manuscript illumination of Gabriel with a trumpet. And before that, in 1382, John Wycliff identified Gabriel as the trumpeter in a religious tract he wrote.[6]

But none of that is specifically biblical. This association between Gabriel and the return of Jesus happens much later (as best I can tell), so I don’t think it influences Luke’s writing.

This is not where I was hoping this research would lead me. I hoped I’d get a stronger sense of why Gabriel is named and a better sense of who Gabriel is. Instead, what I found is a tendency for us human beings to create story and image to fill in the evocative unknown. It’s like when we imagine a big discussion between Joseph and one Bethlehem inn keeper after the next – and all because of a sentence fragment in Luke’s gospel: “because there was no room for them in the inn.”

We do the same with Gabriel. We give Gabriel a trumpet and a special role at the end of time. We give Gabriel wings even though there’s no mention of wings in the scripture. And it’s not just wings. Artists have been especially good at filling in the blanks. Perhaps that’s because the Bible lacks much description.

Both this 14th century Russian icon of Gabriel and this 14th century illumination of the annunciation seem inventive to me. I especially like that Gabriel’s clothing in the illumination are feathers.

This 15th century depiction of Gabriel is, interestingly, feather-free – and look at the color in those wings.

I must say that none of these depictions or any of the others I’ve looked at this week seems to be especially frightening to me. Since the first thing an angel says is, “Do not be afraid,” you’d think they’d be frightening.

There’s a 20th century depiction of the annunciation (it’s one of my favorites) that shows a Gabriel that would be frightening. I also like how Mary is depicted – a simple peasant girl in a simple home on a simple bed.

There’s a story about Gabriel that lingers in the attic of my brain, over in the corner with the Christmas decorations. It’s a story that fills in some blanks. I have no memory of the source of the story. The story is that when God sent Gabriel to Nazareth so that Jesus could be born, Gabriel had to visit a bunch of unmarried women because they kept saying, “No.” The idea of bearing a child outside of wedlock was just too embarrassing for them all. It wasn’t until Gabriel got to the home of young peasant girl that Gabriel heard the “yes” he needed.

I wish I had some great insight for you (and for me) today. Really, all I have are some stray thoughts. I’m still not sure what I believe about angels – about heavenly beings who bear messages from God. And while I’m not certain about heavenly beings, I am certain that human beings can be bearers of God’s messages and God’s love, and that sometimes these human angels have grease under their fingernails.

Maybe you can finish the sermon today by thinking about these two questions:

Who (or what) has been a bearer of God’s message and love for you?

How has the heavenly broken into your reality and filled you with wonder, awe, and/or fear?

_______________

[1] Baruch S. Davidson, “What Are Angels?” Chabad.org, https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/692875/jewish/What-Are-Angels.htm (accessed 7 December 2019).

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Bill Pratt, “When was the book of Daniel written?” Tough Questions Answered,https://www.toughquestionsanswered.org/2016/07/08/when-was-the-book-of-daniel-written/ (posted 8 July 2016; accessed 7 December 2019).

[5] Bauckham, R. J. (1996). Gabriel. In D. R. W. Wood, I. H. Marshall, A. R. Millard, J. I. Packer, & D. J. Wiseman (Eds.), New Bible dictionary(3rd ed., p. 389). Leicester, England; Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press.

[6] “Gabriel,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gabriel (accessed 7 December 2019).

A sermon preached at Niles Discovery Church, Fremont, California,

on Sunday, December 1, 2019, by the Rev. Jeffrey Spencer.

Scriptures: Matthew 1:18-25 and Matthew 2:13-15

Copyright © 2019 by Jeffrey S. Spencer

The experts say that adults typically have four to six dreams a night and that dreams can last for as long as 34 minutes (which strikes me as an oddly specific number).[1] They also say that most of us forget 90 to 99 per cent of our dreams.[2]

We don’t have scientific evidence that conclusively points to why we dream. Some think that our dreams reveal the workings of our subconscious, that they reveal our deep and hidden desires and emotions. Other prominent theories suggest that dreams assist us in memory formation (that they are a time when the events of the day write to disk), that they assist us in problem solving, or that they are simply a product of random brain activity.

I personally subscribe to an “all of the above” theory. I’ve had dreams that I managed to remember that helped me better understand my emotional self after working with them. I suspect that some dreaming not only helps a memory solidify in our brains, but also help us make sense of experiences. I once came up with an approach to an advanced math problem in a dream while I was in college that helped me solve it, and I suspect other interpersonal problems are worked on in our dreams. And I’ve remembered some really weird dreams that make me think they had to be the random product of random brain activity.

I personally subscribe to an “all of the above” theory. I’ve had dreams that I managed to remember that helped me better understand my emotional self after working with them. I suspect that some dreaming not only helps a memory solidify in our brains, but also help us make sense of experiences. I once came up with an approach to an advanced math problem in a dream while I was in college that helped me solve it, and I suspect other interpersonal problems are worked on in our dreams. And I’ve remembered some really weird dreams that make me think they had to be the random product of random brain activity.

Sunday night – actually, early Monday morning – I dreamed I had lost my phone, and then it because my wallet that was missing. I found my wallet in the dream, but it was empty. My driver’s license and credit cards were missing. But then I realized it was my old wallet, so I needed to find my new wallet, which I did, and everything was fine.

I had forgotten to put my phone in my pocket Sunday morning, so I think the dream was related to that experience. And there may have been some emotional stuff going on related to identity (my ID was missing from my wallet). I did solve the problem of my missing wallet in my dream. And maybe some random stuff was happening in my brain, because the new wallet that I found was green, and my wallet in real life isn’t green.

The one thing I can say for sure about my early Monday morning dream is that it wasn’t life changing.

I have had exactly one dream that changed my life – or, I should say, changed my view of death. In this dream I died. Or more accurately, I went from being alive to realizing that I must be dead (because no one can survive walking on lava). The thing that was life changing was realizing how peaceful it is to be dead. While I still have some concerns about dying, about the actual process of moving from this life to the next, I am convinced that whatever comes next, it will be peaceful.

The Hebrews and Jews[3] viewed dreams (at least some of the time) as somehow connected to the supernatural. I say “some of the time” because the record we have is about the dreams that were interpreted as being connected to the supernatural. I don’t know what the equivalent for Abraham would have been to dreaming that it’s the final exam and you haven’t been to the class even once all semester. I’m sure the people of Ur, four thousand years ago, had some type of anxiety dream. Those dreams didn’t make it into the Bible, however, so I’m not aware of evidence that it would have been considered somehow supernatural.

There are a few references in the Bible’s wisdom literature suggesting that some dreams should essentially be ignored as unimportant.[4] Nonetheless, some dreams were certainly seen as connected to the supernatural, and thus they could be both feared and sought after because of their potential bearing on persons and events. Jacob’s dream of angels ascending and descending a ladder between earth and heaven is an example of a dream in scripture that was viewed as being connected to the supernatural.

There are a few references in the Bible’s wisdom literature suggesting that some dreams should essentially be ignored as unimportant.[4] Nonetheless, some dreams were certainly seen as connected to the supernatural, and thus they could be both feared and sought after because of their potential bearing on persons and events. Jacob’s dream of angels ascending and descending a ladder between earth and heaven is an example of a dream in scripture that was viewed as being connected to the supernatural.

The difference between a “dream” and a “vision” in the Bible isn’t completely clear to me. For instance, in the Book of Acts, there are times when someone has a vision and receives a specific direction from God to do something. Like in Acts 9, when Ananias has a vision in which God says to him to go to the home of Judas (not the Judas who betrayed Jesus; a different Judas) and find Saul of Tarsus, and lay hands on him to restore his sight. Perhaps these visions that come from God are like the dreams that come from God in that they offer some direction to do something, the difference being whether the receiver of the direction gets the message while they’re asleep or awake.

Most of the time, visions and dreams seem to be very specific and concrete, but not always. There are two important instances in the Bible when dreams are highly metaphoric and, interestingly, both of these involved kings of non-Jewish countries. The first happens in Genesis. If you’ve read the Jacob saga, you’ll remember that he had twelve sons and the one named Joseph was his favorite. Joseph had two important talents: One was annoying his brothers. The other was interpreting dreams. And he used the second to accomplish the first.

Joseph had dreams that he interpreted to mean that his brothers would bow down to him and his authority. That ticked them off enough to sell him to slave traders. He ended up in Egypt as a slave, and then in prison (I’ll let you read the story for those details). He got out of prison by interpreting first some fellow inmates’ dreams and then Pharaoh’s dreams. Thanks to his interpretive skills, he rose to a position of authority in Pharaoh’s government, and sure enough, his brothers ended up coming to him for help, and bowing down before him. All the dreams in this story were metaphoric and needed interpretation.

Joseph had dreams that he interpreted to mean that his brothers would bow down to him and his authority. That ticked them off enough to sell him to slave traders. He ended up in Egypt as a slave, and then in prison (I’ll let you read the story for those details). He got out of prison by interpreting first some fellow inmates’ dreams and then Pharaoh’s dreams. Thanks to his interpretive skills, he rose to a position of authority in Pharaoh’s government, and sure enough, his brothers ended up coming to him for help, and bowing down before him. All the dreams in this story were metaphoric and needed interpretation.

The second happens in the book of Daniel. In this story, the Babylonian king, Nebuchadnezzar, has a vision or dream and he can’t figure out what it means. Daniel, thanks to some coaching from an angel, interprets the dream.

The thing that is consistent in these stories is the belief that the interpretation of dreams could be accomplished only with God’s guidance. In fact, there are laws in the Torah against false interpreters and false interpretations of dreams. It’s a dangerous thing to claim to know God’s will.[5]

And yet it seems that Joseph (the husband of Mary, not the son of Jacob) knows God’s will for him. The dreams that this Joseph has in Matthew’s introduction to his gospel are very direct and clear and are the revelation of God’s will for him. In the first dream, Joseph finds out that Mary is pregnant. He knows he’s not the father, so he decides to break things off with Mary. He’s a decent enough of a fellow to do this quietly, rather than dragging her in front of some court and accusing her of adultery. And then he has a dream. An angel shows up in the dream and is quite clear with him: “Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”

And yet it seems that Joseph (the husband of Mary, not the son of Jacob) knows God’s will for him. The dreams that this Joseph has in Matthew’s introduction to his gospel are very direct and clear and are the revelation of God’s will for him. In the first dream, Joseph finds out that Mary is pregnant. He knows he’s not the father, so he decides to break things off with Mary. He’s a decent enough of a fellow to do this quietly, rather than dragging her in front of some court and accusing her of adultery. And then he has a dream. An angel shows up in the dream and is quite clear with him: “Do not be afraid to take Mary as your wife, for the child conceived in her is from the Holy Spirit.”

There are four more dreams that follow in rapid succession in the overture to Matthew’s gospel.[6] The second one is a dream the wisemen have. And then Joseph has three more. We heard the next dream Joseph has, the one that comes after the wisemen’s visit, when Joseph is directed to protect his family by fleeing King Herod’s violence and becoming refugees to Egypt. They stay, Matthew tells us, out of their country until it becomes safe to return, when Herod the Great dies. Joseph learns that it’s safe to leave Egypt in a dream, and in the last dream that they shouldn’t return to Bethlehem for safety reasons, so they return to Galilee instead.

Joseph is the actor in the introduction to the Gospel of Matthew. And he acts on God’s instructions communicated in dreams. Joseph has a dream and takes Mary as his wife. She bears a son and Joseph names him Jesus (as the angel is his dream directed). Joseph flees with his family to Egypt and it is in a series of dreams that he determines that it is safe for them to return.

I admit that I’m a little jealous of the Joseph described in these first two chapters Matthew’s gospel. When it comes to decision making, I’d love to get angels showing up in my dreams directing me. I would love to have the big neon sign pointing “This way!” I would love to have that level of clarity about how to best fulfill God’s vision for me and for humanity. But I’ve never had an angel show up in a dream.

In fact, I’ve never had a dream that I remember where I got any sense of how to best make an important decision. And let’s face it, these were big decision Joseph got direction about. Should I marry her? Has home turned into the mouth of a shark and we should flee?[7] Is it safe to return home?

And so it occurs to me that perhaps, if God will not send us angels in our dreams, we must have visions. Perhaps it is our duty, as followers of Jesus, to claim his vision as our own and to use that vision to help us make decisions – individually, in our families, and as a congregation.